[This post first appeared on the WISR blog]

Dorothy Garrod was the first woman to be made an Oxbridge professor. In 1939 she was elected to the Disney Chair in Archaeology at Cambridge University. At that time women were still not allowed to graduate from Cambridge on an equal footing with men, and as such could not vote on university matters, nor serve on the University’s governing council. As a Professor, however, Garrod now had this right. Through the power of her brilliant, world-renowned research, Dorothy Garrod had stormed this last bastion of male academia, nearly ten full years before it was officially ready for her. BOOM!

The myth of the lone hero

It’s pretty easy to make a hero out of Garrod. Her work really was brilliant. She really was a pioneer, leading large excavation projects in the Middle East. And as the first female Oxbridge professor, she paved the way for many more talented women to follow in her footsteps. Add to this contemporary descriptions of her as being “small, dark and alive,” and “like a dry white wine”, and the most beguiling narrative emerges of this tiny, crisp woman – armed only with her mind – taking on the pipes and the port of the male establishment, and succeeding against the odds.

The problem is that framing Dorothy Garrod’s achievements in this way probably says more about us, and the heroes we want, than the reality. And by ignoring the reality, we risk never truly understanding why women like Garrod came to succeed and what this might mean for diversity issues that persist in science to this day.

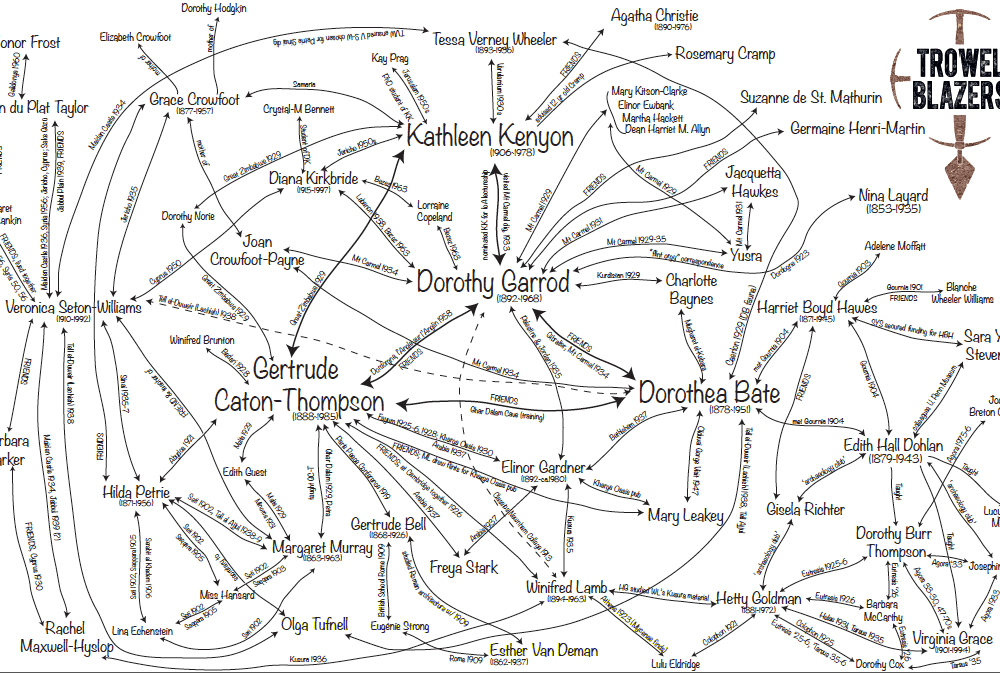

You see, Garrod’s uniqueness as an Oxbridge professor obscures the – perhaps even more surprising – fact that she was very much not unique as a brilliant, respected woman archaeologist in the early twentieth century. Another woman, and friend of Garrod, Gertrude Caton-Thompson had been tipped for (and possibly even offered) the Disney Chair. And Garrod’s career up to 1939 had been characterised by collaborations with other women, most famously at her all-women excavations at the palaeolithic site of Mount Carmel, in Palestine (1929-1934). On top of this, Garrod was a Newnham College fellow – she had been an undergraduate there herself before the first world war, overlapping with the classical scholar Winifred Lamb (later keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the Fitzwilliam Museum), and geologist Elinor Gardner (who became a great friend and collaborator of Gertrude Caton-Thompson, and also went on to work with Garrod). At Newnham, Dorothy Garrod was both part of a community of academic women, and was responsible for training up future generations of the same. She was a key hub in a network of pioneering women archaeologists.

This is where Kevin Bacon comes in. Linking Garrod to Bacon in six steps is more than just a very niche party trick. It provides a window into the large and complex web of connections that existed between early twentieth-century women archaeologists: women who trained each other, collaborated with each other, secured funding and jobs for each other, and who offered each other support, friendship and competition (friendly or otherwise).

Six Degrees of Dorothy Garrod

STEP ONE: DOROTHY GARROD to DOROTHEA BATE

Archaeology is a young science. In 1922, when Dorothy Garrod wrote the book that launched her career (The Upper Palaeolithic Age in Britain, published 1926), there were just 24 professional archaeologists in the UK. In such a small field, an individual can make a large impact – and Garrod’s meticulous, comprehensive work did just that. She combined many lines of evidence to integrate the early British Stone Age with that of continental Europe. One of these lines of evidence was a study of the animal remains found at palaeolithic (“old stone age”) sites – and to do this she was helped by the fossil mammal expert at the Natural History Museum: Dorothea Bate. Bate and Garrod would go on to collaborate repeatedly throughout their careers.

STEP TWO: DOROTHEA BATE to EDITH HALL DOHAN

When Dorothea Bate met Dorothy Garrod she had over 20 years of research experience, and was a well-respected – if poorly paid – scientist. It was on one of her early expeditions, to Crete in 1904, that she met and befriended American archaeologist Edith Hall (later Hall Dohan). Hall was on her first excavation, digging at the Minoan town of Gournia under the direction of yet another pioneering woman archaeologist: Harriet Boyd, the first woman to direct an excavation in Greece. Edith Hall went on to a successful academic career, eventually returning to her alma mater Bryn Mawr to teach in 1921. There she trained up a new generation of classical archaeologists.

STEP THREE: EDITH HALL DOHAN to DOROTHY BURR THOMPSON

Dorothy Burr Thompson studied under Edith Hall Dohan at Bryn Mawr, and like Hall Dohan (and Harriet Boyd) before her, went on to be a fellow at the American School in Athens (1923-5). There she excavated extensively, under the direction of Hetty Goldman (another woman!). In 1934 Burr Thompson became the first woman to be appointed a fellow of the excavations at the Ancient Agora in Athens. She continued to be part of the Agora excavation project into the late 1970s.

STEP FOUR: DOROTHY BURR THOMPSON to JOAN BRETON CONNELLY

In 1975-6, Joan Breton Connelly – then an undergraduate at Princeton; now Professor of Classics and Art History at NYU – worked as Dorothy Burr Thompson’s assistant at the Athenian Agora. This was Breton Connelly’s first excavation experience; she went on to be the director of the Yeronisos Island Excavation, in Cyprus.

STEPS FIVE & SIX: JOAN BRETON CONNELLY to BILL MURRAY to KEVIN BACON

Yes. The actor Bill Murray has a secret alter ego as an archaeologist. He was one of the philanthropic donor-excavators at the Yeronisos Island Excavations. And, of course, Bill Murray appeared in Wild Things with Kevin Bacon.

So there you go: Dorothy Garrod to Kevin Bacon in six steps, four of which were through women archaeologists, taking in a century of archaeological research in the Mediterranean.

Six Degrees – So What?

These connections only scrape the surface of the number of women working in archaeology from its inception. It would take hundreds of thousands of words to capture their achievements adequately – but it only takes a look at my network figure above to immediately grasp the scope of the number of stories still untold.

This figure came out of research for a chapter that TrowelBlazers has contributed to the Finding Ada book A Passion for Science. TrowelBlazers – a blog celebrating the contribution of women to archaeology, palaeontology and geology – was born out of righteous indignation that so many women, and their aggregate contribution to research, had been forgotten: one or two women being written out of (popular) history can potentially be dismissed as the chance loss of a rare thing, hundreds cannot.

These pioneering women did face prejudice, and they defied social convention. They had to carve out a niche for themselves, but they weren’t alone: when they weren’t allowed to study alongside men, they started their own colleges; when they weren’t allowed to dig with men, they started their own excavations. And wealth, privilege and connections gave them the power to achieve these things. In doing, they opened up opportunities for other women, and created a critical mass of women – doing top-quality research – who could have a real influence and power in a young discipline.

Today, women hold 46% of UK academic posts in archaeology. In contrast, in the biological, mathematical and physical sciences this figure is just 28%. Could this be a legacy of these early collaborative networks? If so it highlights the importance of social networks, and the emotional, practical and political support they offer, in effecting demographic change.

[You can download a full-resolution version of my Very Incomplete Network of TrowelBlazers from Figshare. Plus citation details are there.]