I am interested in the how and why of evolutionary and environmental change, and I investigate this in living and fossil animals using a variety of lab and field methods, with a big team of international collaborators.

The Evolution of Elephant Molar Morphology (Daphne Jackson Trust)

Clever, social, and very big, elephants have fascinated humans for millennia. The largest living mammal, their evolutionary history parallels our own, over similar timescales: rooted in Africa before dispersing the world over, over the last 10 million years a huge diversity of elephant species evolved as grasslands expanded in a cooling/drying world. Today’s three elephant species in Africa and Asia belie a rich fossil record, global in scope. Many were as big or bigger than living elephants, excepting island populations that evolved to become ‘dwarf elephants’ – some just 1m tall. Remarkable in their own right, through them we can also understand how climatic changes of the past shaped evolution, and our world today.

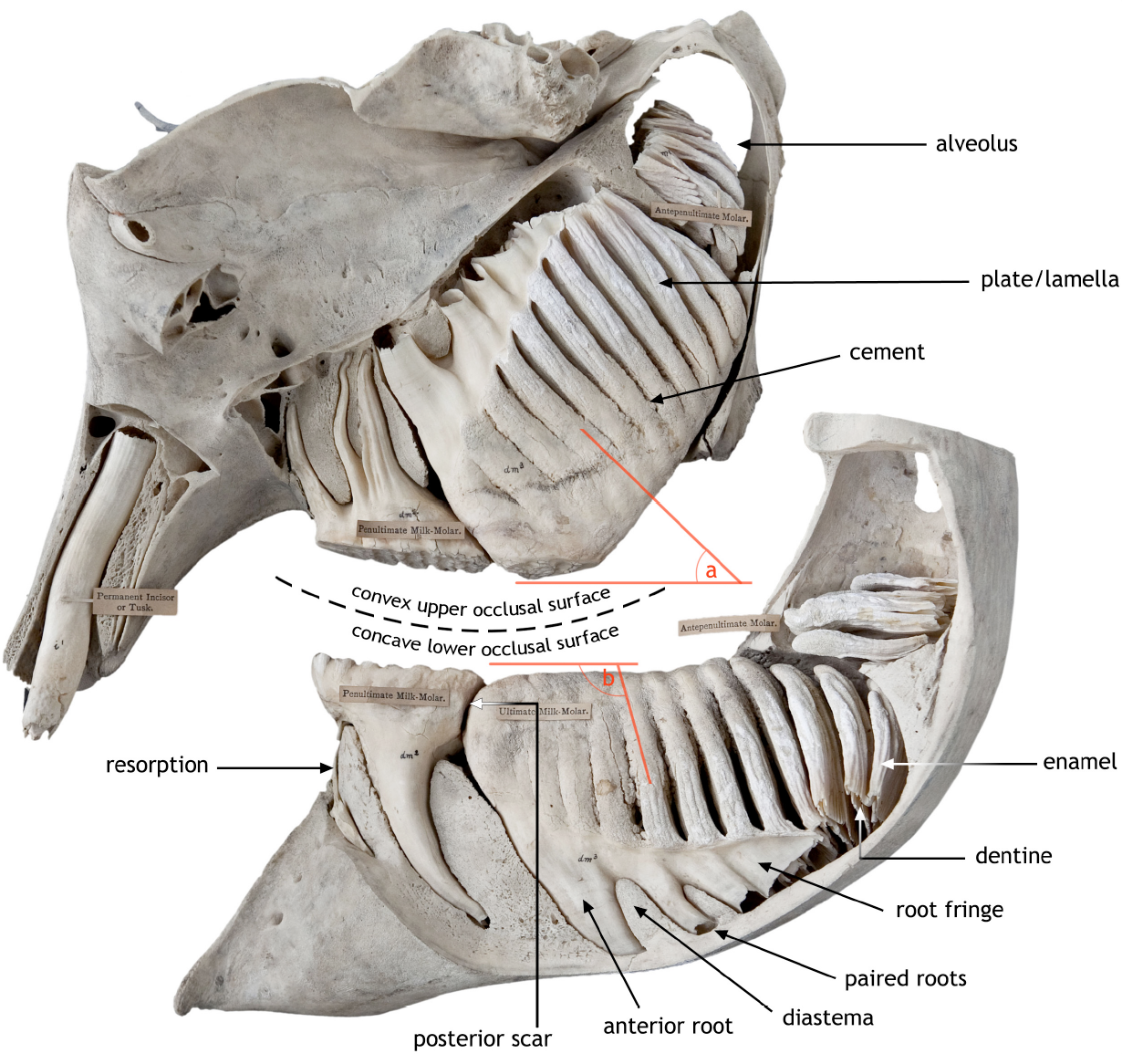

Section through a juvenile Asian elephant skull, showing elephant tooth development. (c) Victoria Herridge

Teeth provide critical characters for reconstructing elephant evolutionary history. From 10 million years ago, elephant teeth evolved to become taller with more closely spaced ‘plates’. This is thought to reflect increased grazing ability but isn’t fully understood. The problem is that elephant teeth are weird. In contrast to other mammals (including humans), where milk teeth are replaced vertically, elephant cheek teeth grow horizontally from the back of the jaw, moving forward like a conveyor belt as the tooth in front wears down. In other mammals, not accounting for tooth growth and development can mislead evolutionary studies. Is the same true of elephants, given their unusual teeth? And could this alter our understanding of how climate change affected elephant evolution?

To find out, I will investigate whether elephant teeth fit the typical mammalian pattern of tooth development, and how this is linked with tooth size and shape. Because body size is tied directly to growth, and a defining character of elephant biology, I will compare this in island dwarf- and full-size elephants. Studying tooth development normally requires laboratory experimentation inappropriate for large and intelligent animals like elephants. However, the extended growth of elephant teeth provides an unusual opportunity to use the fossil record to answer these questions. This vital new data will help to ground-truth classic theories of evolution and adaptation, the impact of climate change, and enhance our understanding of the beautiful complexity of the natural world.

Mammoth Fauna from Siberian Permafrost

The cave lion cub, Sparta, in the walls of the tusk-hunter’s tunnel. (c) Victoria Herridge

I work with colleagues at the Yakutian Academy of Sciences to understand the evolution and ecology of Ice Age animals and plants from the Mammoth Steppe — an ecosystem with no modern parallel, but which was once the world’s most extensive biome. In recent years, the rate of discovery of exquisitely preserved remains (often with flesh, fur and internal organs intact) has accelerated owing to increased levels of prospecting for mammoth ivory, aka “tusk hunting.” By carrying out morphological, genetic and isotopic investigations into these unique and precious remains, we aim to better understand the animals and ecological processes of this lost world across the changing climatic conditions of the Ice Age.

See our recent paper on a 44,000 year old horned lark from the Belaya Gora region of Siberia here.

Insular Dwarfism and Gigantism (Natural Environment Research Council/Leverhulme Trust)

When full-sized elephants from the European mainland — huge 4m tall mammoths or the equally big straight-tusked elephants — became isolated on islands like Sicily, Malta, Sardinia, Crete and Cyprus (as well as many Greek islands!), their evolutionary response was always the same: they evolved to become smaller, sometimes as small as just 1m tall as an adult. And they weren’t alone – deer and hippos on the same islands also became dwarfed, while rats and dormice evolved into new giant forms.

The tibia (shin bone) of an adult dwarf elephant from Spinagallo Cave in Sicily. This would have belonged to an elephant that was less than 1m-tall.

I’m trying to find out when, why and how dwarf elephants evolved. It all started with my PhD at UCL (which is freely available to download here), and continues at the Natural History Museum, London, thanks to funding from the Natural Environment Research Council (2009-2013) and the Leverhulme Trust (2014-2016).

I study the fossilised remains of dwarf elephants that are kept in museums like the Natural History Museum. Most of these fossils were excavated over 100 years ago, when the techniques we use to date fossils hadn’t been invented. As a consequence we don’t know how old, geologically speaking, the dwarf elephants fossils are – a vital piece of information if we want to understand why, or how quickly, they evolved.

See my recent publications on evolutionary rates in dwarf elephants here; and morphological change in Giant Dormice here and here.

So I scour the archives of Victorian and Edwardian pioneers (like my hero Dorothea Bate) for clues about where they dug up their dwarf elephant fossils, and then use these clues to follow in those pioneers’ footsteps. With colleagues from the across the UK, Greece, Italy and Cyprus, I’ve been revisiting these sites to use modern methods like Uranium series dating, Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating, Electron Spin Resonance dating, and Amino Acid Racemisation to discover just exactly when different species of Mediterranean elephants evolved.

In pursuit of dwarf mammoths. Following in Dorothea Bate‘s footsteps in Crete. Photo (c) Dr David Richards.

Read my paper identifying extreme insular dwarfism in a mammoth from Crete here.

I love your views on paleontology of extinct megafauna. i wonder if dwarfism might be a possible way to ameliorate modern pachiderm issues in both India and Africa. As to cloning mammoths, they do seem to be suited to re-establish a more viable ecosystem in the taiga and tundra areas of northern Asia. We are now entering a strange conjunction in time where humanity is causing extinctions and almost capable of recreating lost species.

I have viewed the evidence that the Pleistocene megafauna extinction event may have been caused by an impact event around the beginning of the Younger Dryas onto the North American icecap. (an accidental, non systemic extinction event) I understand this is controversial, but seeing the larger extinction events at this time in non glaciated northern Siberia, I feel the research deserves merit. It pleases me that we may somehow correct a unfortunate cataclysmic loss.

The main problems I feel are that Pachiderms seem to be an extreme Matriarchical Cultural society. Knowledge is past from generation to the next through the female line. Once this is disturbed or broken, I don’t understand if it can be re-established.

i am not a scientist, I retired as the postman to Portland Oregon Zoo. They have Elephants and a very nice Mastodon skeleton. They were brousers, not grazers like Mammoths or most elephants. But I miss them all.

thanks for your work

Tom Esau

LikeLike